Jacques Berland Exhibition. In Praise of a Little Master

From December 17th 2022 to march18th 2023

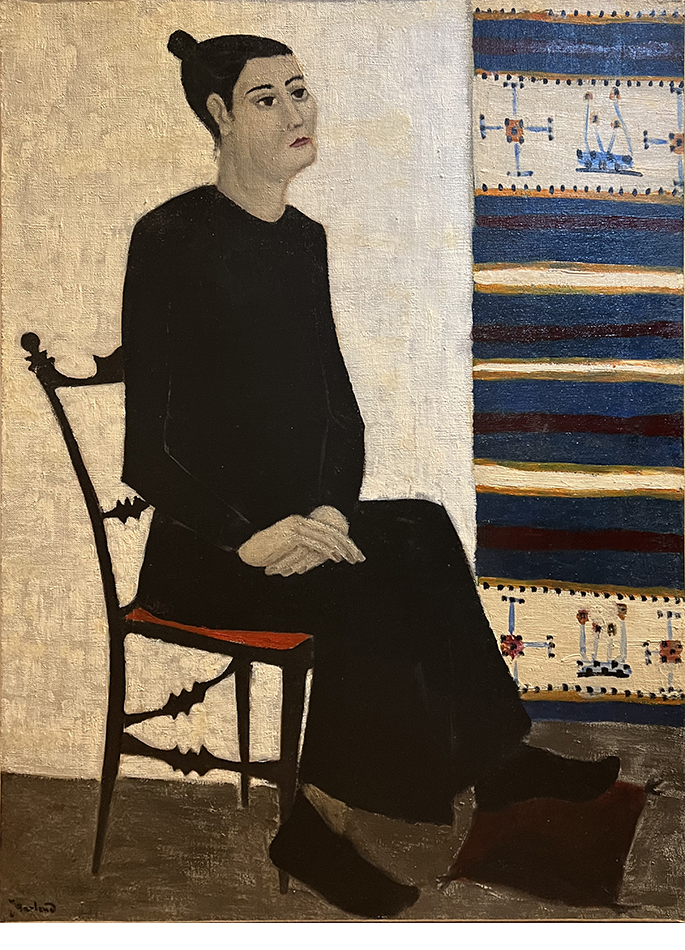

It was in 1955 ; he was 37 years old. We imagine him as he must have been at that time, and as he painted himself in a superb self-portrait: a man with black hair, a fine face, of discreet elegance. In detail, the grey of a suit, the collar of a shirt, the knot of a tie — but mostly, in order to stare us soflty, two big dark eyes under heavy eyelids, two gigantic eyes that seems astonished…

Exhibited works

In Praise of a Little Master

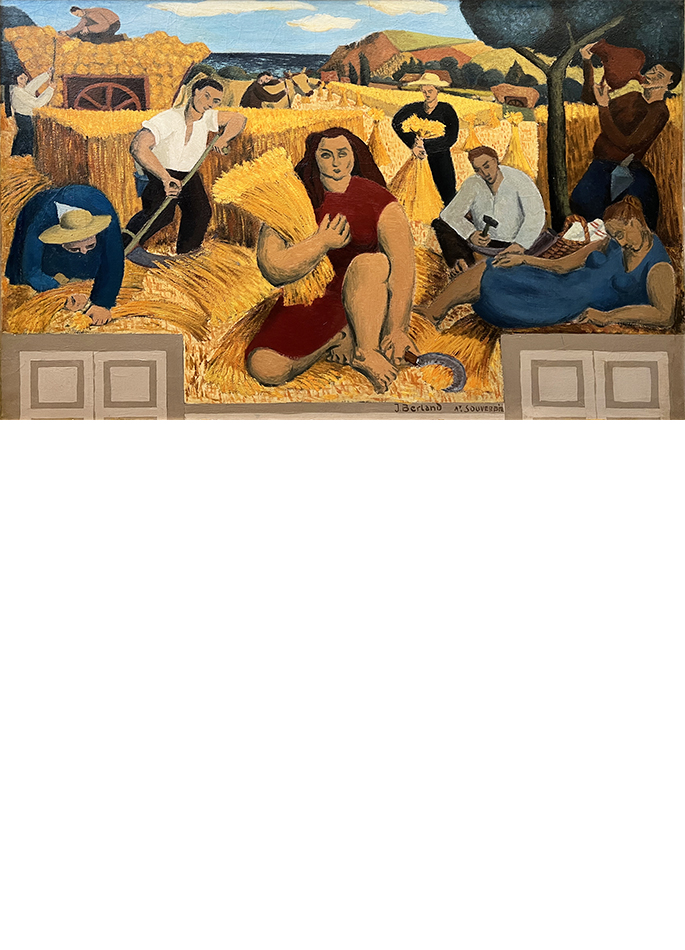

It was in 1955 ; he was 37 years old. We imagine him as he must have been at that time, and as he painted himself in a superb self-portrait: a man with black hair, a fine face, of discreet elegance. In detail, the grey of a suit, the collar of a shirt, the knot of a tie — but mostly, in order to stare us soflty, two big dark eyes under heavy eyelids, two gigantic eyes that seems astonished… Does it mean that Jacques Berland, in fronf of the mirroras well as in front of his admirers, was evaluating the path he had taken? Because it was there from then on: a noticed talent, to whom the Charpentier gallery had asked to take part to the ‘École de Paris’ exhibition… For those who do not know, or those who have forgotten, it is appropriate to recall here what represented the Chaprentier gallery in the middle of the 20th century : one of the best addresses in the art world! A house that prided itself on stubbornly revealing young painters, and surrounding them with the supreme masters. Thus Jacques Berland tasted the happiness of hanging his paintings alongside Picasso, Buffet, Utrillo, Van Dongen, Vlaminck, Staël, Bazaine, Manessier and Vasarely. He was launched.

But launched towards what? If he had been asked the question, for sure this farmer’s son, born in Pré-Saint-Évroult, in Eure-et-Loire, would have had a hard time answering… What did he want indeed? To paint. And thus to join the history of painting, which he knew better that anyone, studying it continuously in the museums and books. So much so that from 1962 onwards, this man who had remained a prisoner of war in Germany for five years, from 1940 to 1945, and whose wartime godmother was the devoted and attentive Marie Laurencin, so much so that from 1962 onwards, the very erudite Jacques Berland was to become a lecturer at the national museums, with a predilection for the Louvre! Are we to understand that he no longer believed in his own career?

Or should we say, as we think we should, that this exceptionally demanding artist had reached his peak? Still, at the age of 44, despite a laudatory press and several awards, Jacques Berland made the choice to give up painting. In other words, the choice not to copy oneself. Not to enter a system. Not to lose sight of some kind of absolute. Commenting on this decision in 2005, when the work of this authentic little master was rediscovered, Jean-Marie Tasset, former director of the art department of Le Figaro, would sign this formula: « For the idea that I have of painting, I find it salutary that Jacques Berland has chosen to remain free ».

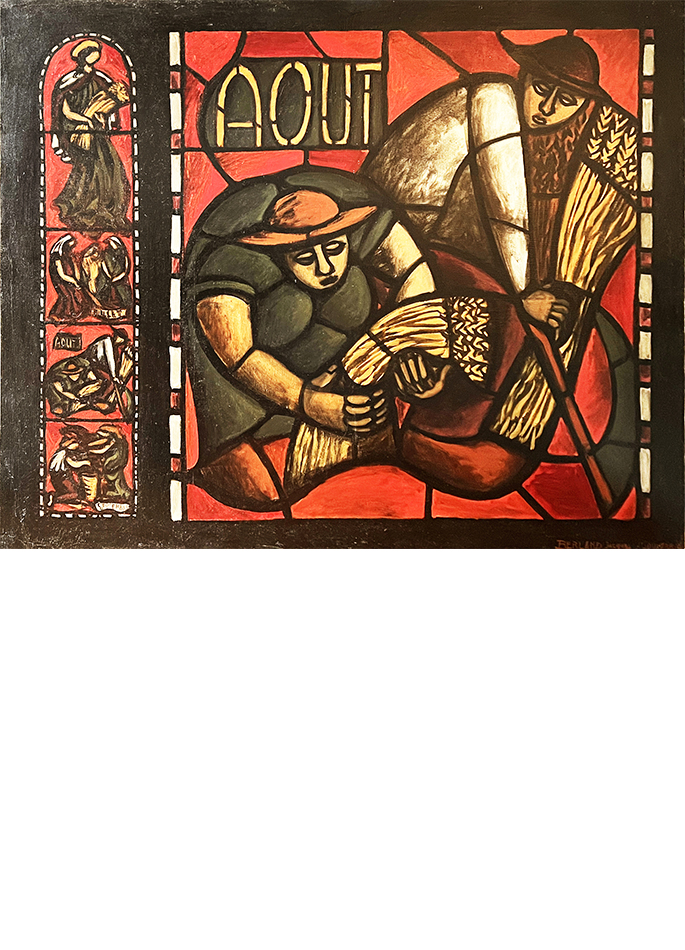

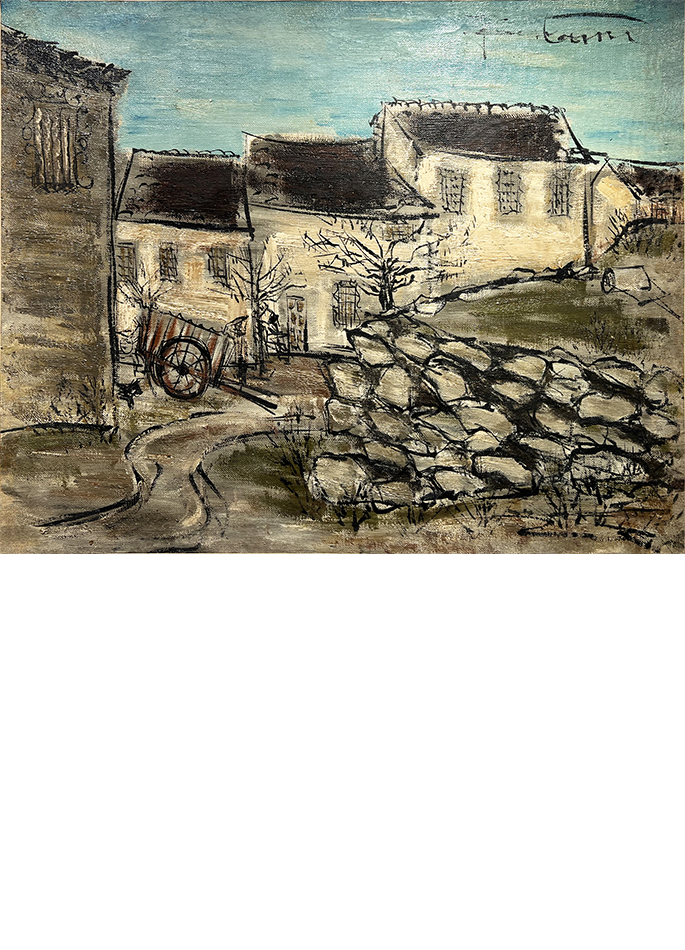

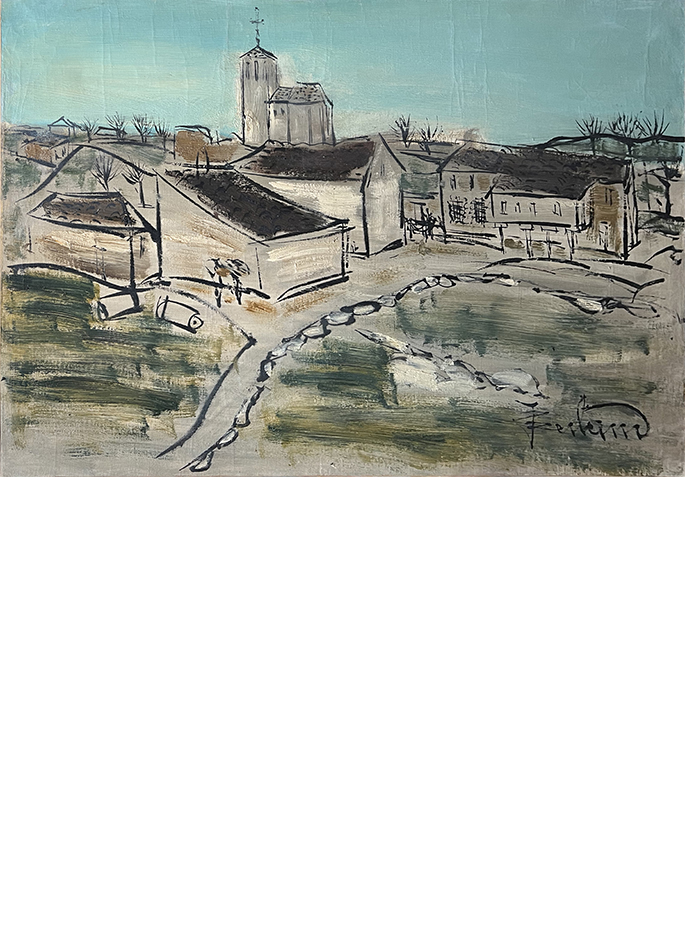

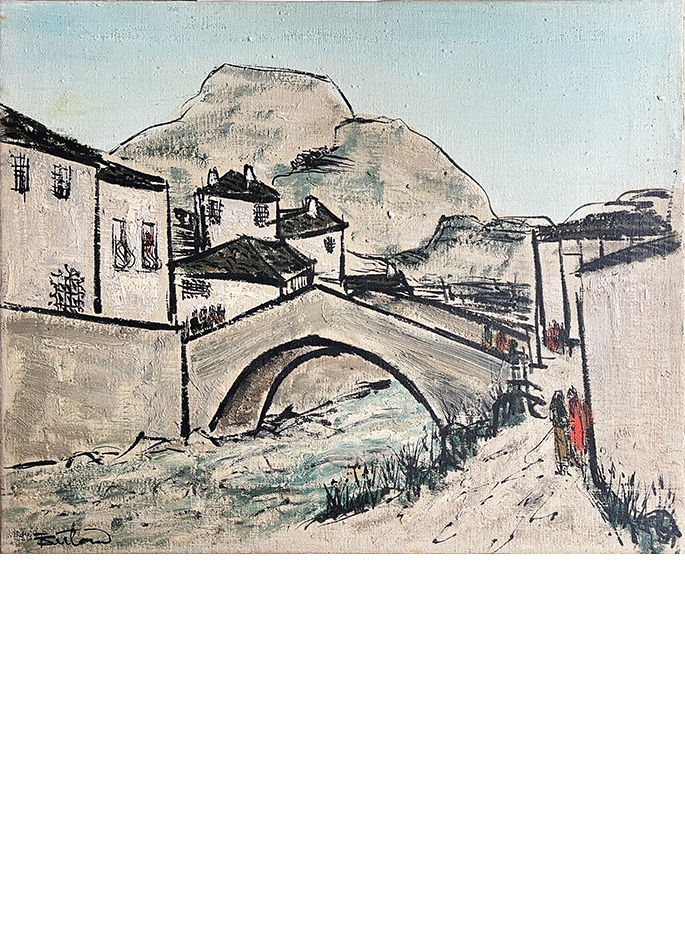

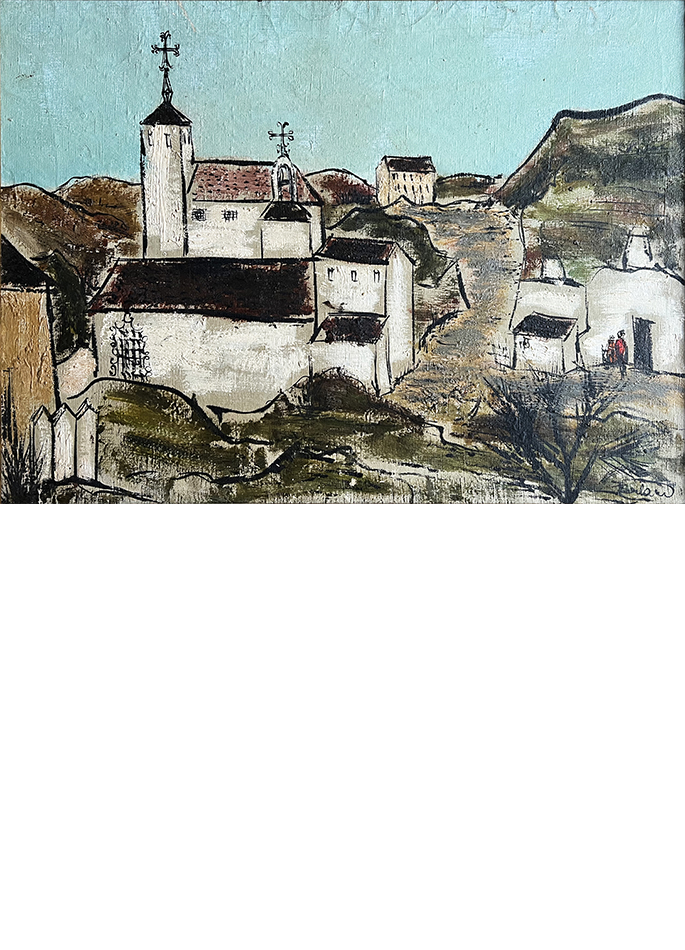

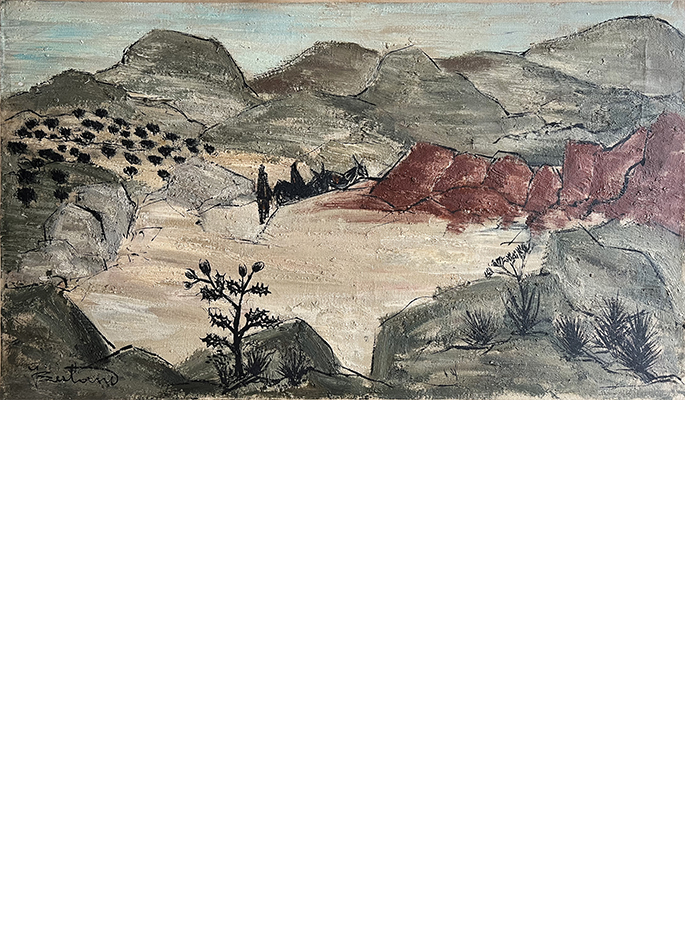

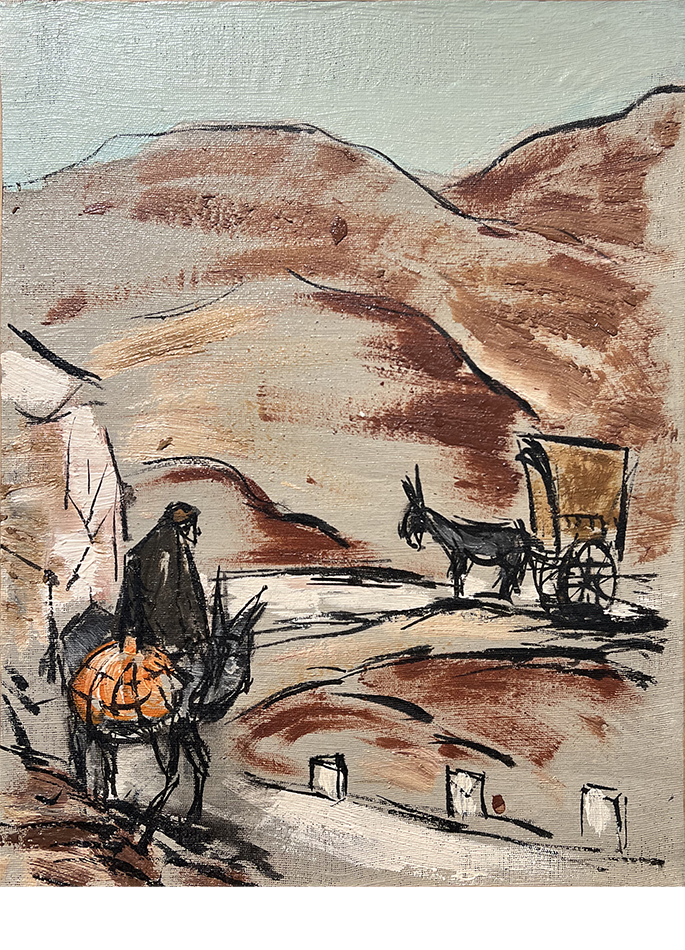

What did he leave behind, after fifteen years of slow and passionate work? A thousand sketches, most of them born in Jean Souverbie’s studio, his teacher at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris. Numerous drawings, including inks and sanguines. Some watercolors, some gouaches. And then, of course, hundreds and hundreds of oil paintings… Still lifes. Portraits. Indoors scenes. Landscapes. Paintings that relentlessly demonstrate the solidity of his line, served by a curious, indomitable spirit. This is particularly true of the Spanish period, which allowed Jacques Berland to render, in a personal and powerful style, the arid land of the mountains of Old Castile. A firm, noble touch, similar to that of the Buffet of the fifties and sixties (the only one pictorially interesting). And a deliberately restricted palette, as if it were a question, each time, of sticking to the essential. Jean-Marie Tasset was definitely right: « a sensitive, inspired hand, which speaks its own language, and which we listen to, subjugated.

Christophe Penot

Art editor